From @OpenAccessArch over at http://dougsarchaeology.wordpress.com comes a simple, yet important and engaging question:

Why blogging? – Why did you, or if it was a group- the group, start a blog?

This is part of a so-called Blogging Carnival in the run up to next year’s SAA. So here goes…

The immediate answer is straightforward enough. I started my – subsequently rather neglected – blog because I wanted a platform where I could post personal musings and viewpoints, of generally low scholarly import, which I would not expect any peer-reviewed environment to publish, and probably would not want them to. Also, as the years advance and the brain cells retreat, having an archive, however irregular and infrequently accessioned, of what I was thinking about a particular subject at a particular time, is inherently useful. For example, I was having a discussion on Friday last week about the A G Leventis Cyprus Gazetteer project and its software requirements: we touched on the difficulties of defining lines between historic territories for which there were and are no contemporary maps (for example the later prehistoric periods in Cyprus). I remembered that I had blogged on a similar question that arose in the CHALICE project three years ago or so. Simply as an aide memoire of how we approached the problem back then helped a lot.

However, Doug’s question raises a deeper issue about ‘why blog?’, as opposed to ‘why do I blog?’ I was taken back to my first-year garret at Durham University, where – in 1995, before the ubiquity of email, before the e-publishing revolution (has there been one?) and, certainly, before Web 2.0 – I read Paul Bahn’s ‘Bluffer’s Guide to Archaeology’. One thing from this terrific little book that stuck with me was Bahn’s railing against those who dug but did not publish. Excavation was the experiment that destroyed its subject, not to publish your results promptly was (and is) an abdication of a sacred responsibility: Bahn spoke of an (unnamed) professor, a leader of his field, who had published nothing for decades as being ‘the clot that blocks the system’. But since 1995, the whole concept of ‘publishing’, never mind ‘scholarly publishing’ has been transformed out of any possible recognition by the web. While I doubt that anyone attending SAA needs to be told this, the question of ‘why blog’ in archaeology makes me wonder if we have really thought through the issues that change has wrought for our subject in as much detail as they require. In some ways perhaps we have. The thoroughly excellent Journal of Open Archaeological Data has bought us the concept that (digital) data can be published alongside scholarly articles, provided they are Open Access, and in a trusted repository which has a long term sustainability plan, and evidence of durability in the future.

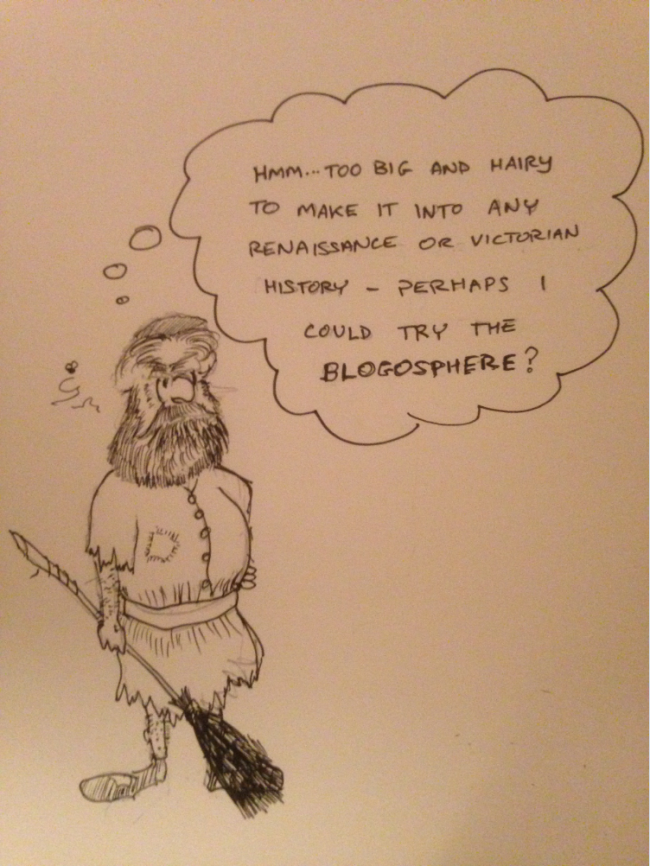

But you only have to look at the mass of links the Doug alone has identified to see that any the age of sourcing archaeological discourse to only ‘professional’ or ‘official’ channels is long past. Intelligent and informed comment and analysis sits alongside the great mass of everything out there. While blogging will never, and should never, try to replace scientific documentation of archaeological site data, its very informality can drive interest in the quirky, the unusual, in subjects neglected by the scholarly discourse. It moves us even beyond the Hodderian notion of ‘multivocaility’, allowing a platform not merely many voices, but the many narratives that those voices tell. This has happened elsewhere in the Digital Humanities – witness Melissa Terras’s work on resource creation via amateur digitisation, which seeks out those topics neglected by official memory institutions. What is archaeological blogging but the ‘amateur’ – in the primary sense of the word – done for love – digitzation of ideas, outside the formal framework of documentation and publication?

Most of us can probably agree that the writing is on the wall (it has been for decades) for the Gibbonesque views of the past, a past told through the elite and literate eyes. In their marvellously entertaining UnRoman Britain (2010, The History Press), Miles Russell and Stuart Laycock note that “[i]t is perhaps the high visibility and obvious distinctiveness of Rome’s archaeological footprint that has caused disproportionate focus upon things that are more ‘Roman’ than the more ‘normal’ aspects that are, to coin a phrase, ‘UnRoman’” (21). Blogging, and the integration of other kinds of social media with the archaeological discourse, provide space for the discussion of such perspectives (there are some fantastic examples of this – eg Rita Roberts’s blog and Bones Don’t Lie), and encourage the process of re-evaluation and scrutiny of established narratives.

So – blogging in archaeology means we do not have to extend the monolithic method-based systems which have bought us the established narratives by which we have come to know both the near and distant past, rather it allows us to expand (on) them by allowing those who are curious enough to form alternative narratives. Ian Hodder’s dictum that ‘interpretation occurs at the trowel’s edge’ may still hold true, but the changing nature of archaeological data and publishing means it can occur on the keyboard too. And this is what the SAA blog carnival is such a great idea.

3 thoughts on “Why blog?”